Discovery of two exoplanets that may be mostly water

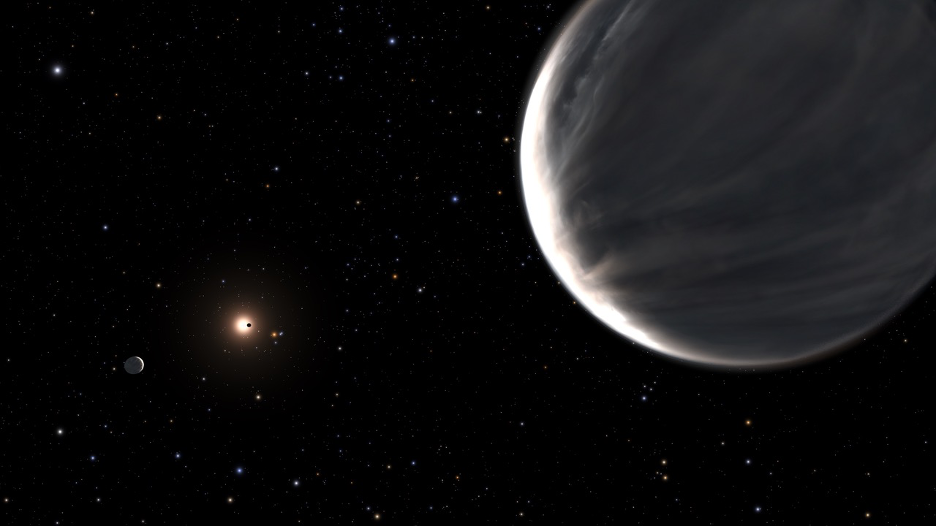

A team led by Université de Montréal astronomers and members of the Centre for Research in Astrophysics of Québec (CRAQ) has found evidence that two exoplanets orbiting a red dwarf star are “water worlds,” planets where water makes up a large fraction of the volume. These worlds, located in a planetary system 218 light-years away in the constellation Lyra, are unlike any planets found in our solar system.

The team, led by PhD student Caroline Piaulet of the Trottier Institute for Research on Exoplanets (iREx) at the Université de Montréal a member of the CRAQ, published a detailed study of a planetary system known as Kepler-138 in the journal Nature Astronomy today.

Piaulet, who is part of Björn Benneke‘s research team, observed exoplanets Kepler-138c and Kepler-138d with NASA’s Hubble and the retired Spitzer space telescopes and discovered that the planets – which are about one and a half times the size of the Earth – could be composed largely of water. These planets and a planetary companion closer to the star, Kepler-138b, had been discovered previously by NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope.

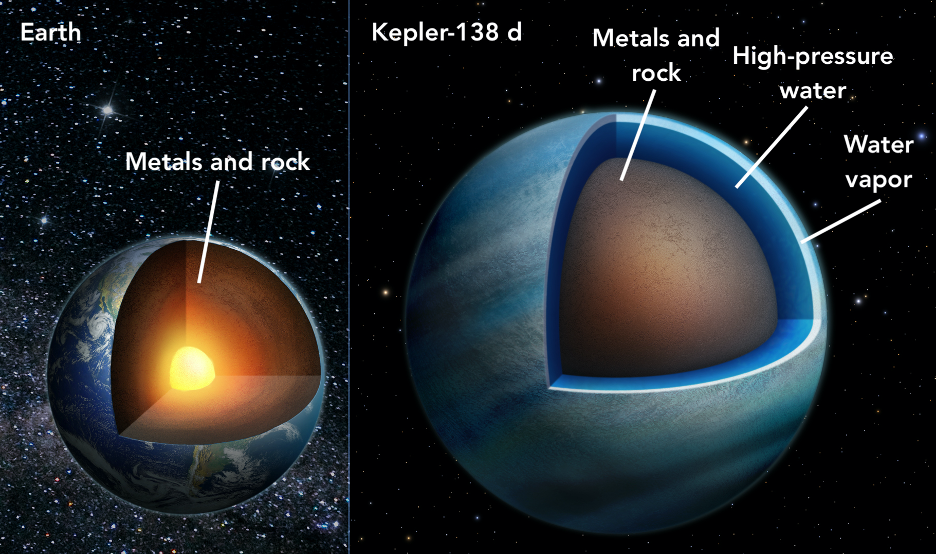

Water wasn’t directly detected, but by comparing the sizes and masses of the planets to models, they conclude that a significant fraction of their volume — up to half of it — should be made of materials that are lighter than rock but heavier than hydrogen or helium (which constitute the bulk of gas giant planets like Jupiter). The most common of these candidate materials is water.

“We previously thought that planets that were a bit larger than Earth were big balls of metal and rock, like scaled-up versions of Earth, and that’s why we called them super-Earths,” explained Benneke. “However, we have now shown that these two planets, Kepler-138c and d, are quite different in nature: a big fraction of their entire volume is likely composed of water. It is the first time we observe planets that can be confidently identified as water worlds, a type of planet that was theorized by astronomers to exist for a long time.”

With volumes more than three times that of Earth and masses twice as big, planets c and d have much lower densities than Earth. This is surprising because most of the planets just slightly bigger than Earth that have been studied in detail so far all seemed to be rocky worlds like ours. The closest comparison to the two planets, say researchers, would be some of the icy moons in the outer solar system that are also largely composed of water surrounding a rocky core.

“Imagine larger versions of Europa or Enceladus, the water-rich moons orbiting Jupiter and Saturn, but brought much closer to their star,” explained Piaulet. “Instead of an icy surface, Kepler-138 c and d would harbor large water-vapor envelopes.”

Researchers caution the planets may not have oceans like those on Earth directly at the planet’s surface. “The temperature in Kepler-138c’s and Kepler-138d’s atmospheres is likely above the boiling point of water, and we expect a thick, dense atmosphere made of steam on these planets. Only under that steam atmosphere there could potentially be liquid water at high pressure, or even water in another phase that occurs at high pressures, called a supercritical fluid,” Piaulet said.

Recently, another team at the University of Montreal found another planet, called TOI-1452 b, that could potentially be covered with a liquid-water ocean, but NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope will be needed to study its atmosphere and confirm the presence of the ocean.

A new exoplanet in the system

In 2014, data from NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope allowed astronomers to announce the detection of three planets orbiting Kepler-138, a red dwarf star in the constellation Lyra. This was based on a measurable dip in starlight as the planet momentarily passed in from of their star, a transit.

Benneke and his colleague Diana Dragomir, from the University of New Mexico, came up with the idea of re-observing the planetary system with the Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes between 2014 and 2016 to catch more transits of Kepler-138d, the third planet in the system, in order to study its atmosphere.

While earlier NASA Kepler space telescope observations only showed transits of three small planets around Kepler-138, Piaulet and her team were surprised to find that the Hubble and Spitzer observations suggested the presence of a fourth planet in the system, Kepler-138e.

This newly found planet is small and farther from its star than the three others, taking 38 days to complete an orbit. The planet is in the habitable zone of its star, a temperate region where a planet receives just the right amount of heat from its cool star to be neither too hot nor too cold to allow the presence of liquid water.

The nature of this additional, newly found planet, however, remains an open question because it does not seem to transit its host star. Observing the exoplanet’s transit would have allowed astronomers to determine its size.

With Kepler-138e now in the picture, the masses of the previously known planets were measured again via the transit timing-variation method, which consists of tracking small variations in the precise moments of the planets’ transits in front of their star caused by the gravitational pull of other nearby planets.

The researchers had another surprise: they found that the two water worlds Kepler-138c and d are “twin” planets, with virtually the same size and mass, while they were previously thought to be drastically different. The closer-in planet, Kepler-138b, on the other hand, is confirmed to be a small Mars-mass planet, one of the smallest exoplanets known to date.

“As our instruments and techniques become sensitive enough to find and study planets that are farther from their stars, we might start finding a lot more water worlds like Kepler-138 c and d,” Benneke concluded.

To learn more

The article “Not all super-Earths are rocky planets: evidence for a warm-temperate volatile-rich water world” was published in Nature Astronomy. In addition to Caroline Piaulet and Björn Benneke (iREx, UdeM, Canada) and Diana Dragomir (University of New Mexico), the team includes co-authors from France, USA and Austria.

Scientific contacts

Caroline Piaulet

Ph.D. Student

Trottier Institute for Research on Exoplanets, Université de Montréal

438-499-2240

caroline.piaulet@umontreal.ca

Björn Benneke

Professor

Trottier Institute for Research on Exoplanets, Université de Montréal

bjorn.benneke@umontreal.ca

514-578-2716

Contact media

Frédérique Baron

Media relations

Centre for Research in Astrophysics of Quebec

frederique.baron@umontreal.ca

About the Centre for Research in Astrophysics of Quebec

The Centre for Research in Astrophysics of Quebec (CRAQ) brings together all the astrophysicists in Quebec. Nearly 150 people, including some fifty researchers and their students from Université de Montréal, McGill University, Université Laval, Bishop’s University, Cégep de Sherbrooke, Collège de Bois-de-Boulogne and a number of other collaborating institutions are part of the cluster. The CRAQ is under the direction of Davif Lafrenière of the Université de Montréal. The CRAQ is one of the strategic clusters funded by the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Nature and Technologies (FRQNT).

Additional Links

- Scientific paper (Nature Astronomy, version open source)